- Advertise

-

Subscribe

The Underworld of Post-Mortem Musician Management

There’s something inside humans that just feeds off of tragedy.

We can’t get enough of the stuff. Shocking stories and terrible tales have a stranglehold on our imagination.

In the music biz, this grim fascination manifests itself in mysterious ways.

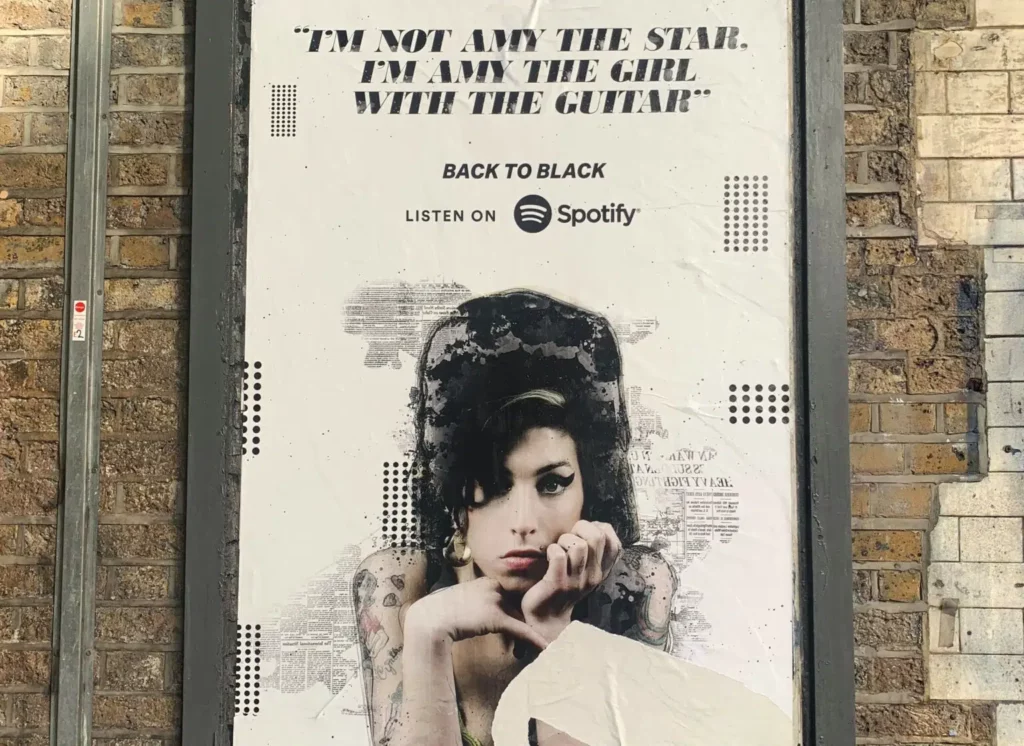

When an artist dies suddenly, you can bet that their streams will sky-rocket – and don’t get us started on what happens when they die in tragic circumstances. We’ll make them a cult sensation, maximizing their afterlife earnings. Maybe even making them more popular than they were before they passed away.

Nothing is more bitter-sweet than artists who reached their heyday only when they can’t cherish it anymore. But nothing screams authenticity more than musicians coping with the grim prophecies conveyed in their hard-hitting lyricism.

It’s just how the late Michael Jackson summarized it – “we don’t stop til’ we get enough.”

And it seems like we’ve never quite had our fill.

We keep them alive in our memories – and our depleting bank balances

We hold on tight to the stars we’ve loved and lost. Because it feels like you got ghosted by your favorite artist – only worse since this silent treatment is rather permanent than a toxic dating trait. It’s heart-wrenching. It shatters your soul.

Just like in any other relationship, our human drive gets stubborn enough to refuse to let go, whatever the cost.

Big music bosses tap into that bullheadedness. Those managing dead musicians keep pushing them forward through PR, social media and revival acts long after they’ve gone, making endless cash streams off of memorial re-releases and never-heard-before best bits.

Dead musicians outsell the living ones because those marketing stunts keep them alive in our memories and depleting bank balances.

We buy into the idea that remembering a dead artist through our wallets is the go-to way to worship a creative mind that’s no longer with us. Why wouldn’t we, when that’s the narrative being sold to us?

But we’re not alone in our somewhat cynical interest in what’s really going on with post-mortem earnings.

Forbes releases a yearly list of the top-earning dead celebrities. Surprise, surprise, Michael Jackson reigns supreme pretty much every year.

We’ll just say this – it’s eye-opening to see how lucrative being dead can be.

Grieving families vs. big corporations

There’s one thing that Forbes notes while post-mortem marketing campaigns neglect to mention, and that’s exactly where the money we spend is actually going.

If an artist’s music is owned by their label (as with the infamous Taylor Swift vs. Big Machine Records dispute), they have the legal right to distribute and profit from it.

Naturally, this has caused some pretty huge feuds over the years between grieving families and big corporations.

Take Aaliyah as an example. The R&B artist’s back catalog has been released this year, despite fans calling for it for the past two decades.

Several false starts with the release were curtailed by the public disapproval from Aaliyah’s estate – run by Aaliyah LLC on behalf of her mother and brother, Diane and Rashad.

But it was released because Aaliyah’s uncle owned the rights to it. Legally speaking, if he wants to continue doing so for the next 50 years or so, he is more than free to do it.

This is far from being a fresh music business concept, especially since artists’ copyright has recently been extended to cover the 70 years following their death. In this murky socio-cultural climate, saying that dead musicians are a highly-lucrative business would be an understatement.

Big corporations are not the only ones to benefit from dead musicians

But this isn’t to say that it’s always the multi-billion dollar music empires that profit from post-mortem releases.

Artists can transfer their music’s rights (and profits) to whomever they wish. Michael Jackson left his entire estate – anywhere between $110 million to $1.125 billion – to his mother and three children, controversially bypassing his eight siblings.

This doesn’t mean the family gets the full share of their deceased loved one’s earnings – even if they’ve been left to them.

According to Mark Roesler – also dubbed ‘the king of dead-celebrity lawyers’ – post-mortem estates are much more complex than that.

It’s a lucrative gig for everyone involved

The estate lawyer gets a cut. The tax office gets a cut. Charities get a cut sometimes, too. Even the marketing team needs to be taken into account when profits get divided.

Then you’ve got the record labels swooping in to sign new release deals to make the most of the post-mortem sales boom – which often exploits grieving families with little knowledge of what’s been thrust upon them.

To cut a long story short, when you pay for a dead artist’s output, there are so many beneficiaries it’s not clear who you’re paying and what you’re paying for.

The only clear-cut thing is that it’s a lucrative gig for everyone involved.

Sure, the motives for remarketing dead musicians, keeping their Instagram presence afloat, and managing their music industry journey beyond lifetime differ depending on who you speak to.

Just because it’s profitable to keep a musician relevant, it doesn’t mean there aren’t any underlying reasons to do so – be it the pure desire to carry on their legacy, raise money for a good cause, or ensure their music imprint is far from being dusted.

It’s a mixture of factors – but financial profit is certainly one of them.

Call us cynical or call us realistic. Whatever you think, it is hard to deny that the world of post-mortem music management has a hell of a lot of cash in it – even when it seems to be all about protecting memories over earning money.