- Advertise

-

Subscribe

When Musicians Die, Their Songs Live On

Before he died, rapper Pop Smoke had about 5 million streams worldwide.

Fast forward to the day after his death and the dead musician’s stream count sat at 24.7 million. His iconic song, Better have your gun, had seen a spike in listeners of a whooping 783%.

But his posthumous rise to fame wasn’t out of the ordinary.

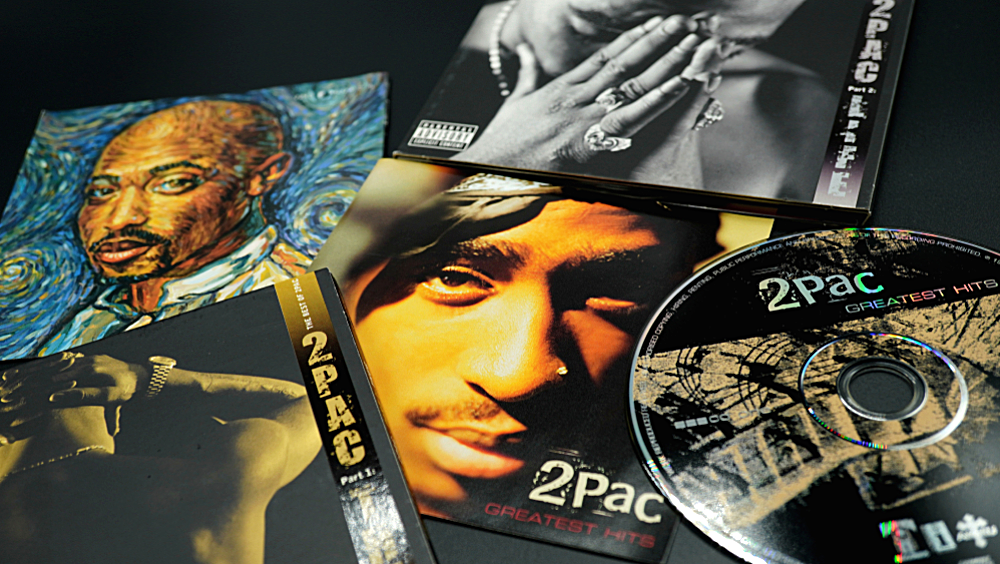

US rapper, XXXTentacion, garnered an extra 50 million listeners following his untimely death. Mac Miller’s streaming count went up by a massive 970% after the hip-hop artist’s accidental overdose. Songs by dead musicians seem to skyrocket among the listeners after the artist’s demise.

There’s something within us that just can’t help but gravitate towards tragedy. As one stand-up comedian put it on a Quora thread discussing Pop Smoke’s troubling passing:

“The sad truth is that if you aren’t an insanely popular artist, dying is the most logical ‘career’ choice.”

But it’s not lesser-known dead musicians who see their record sales jump when they’re no longer around to cherish it – global megastars get the same treatment.

In the decade after his death, the problematic king of pop Michael Jackson, raked in 5.9 billion on-demand streams of his song catalogue – and that is only in the US alone.

When a singer dies, there’s a cultural reset. We rally around them in death as we never did before in life.

Posthumous album releases get record-breaking sales. In memoriam films and biopics have audiences queuing up around the block for their premieres.

Call it paying homage, call it morbid fascination. Whatever it is, it’s just how we react when a star is taken from us too soon.

It helps us to reconcile that which is uncontrollable with our need to remain in control

According to psychiatrist Dr. David Henderson, when we hear about something tragic, we find ourselves morbidly fascinated by it. We’re enacting a process of facing our fears without having to go through any of the trauma.

As he revealed in an interview with NBC:

“Witnessing violence and destruction gives us the opportunity to confront our fears of death, pain, despair, degradation and annihilation while still feeling some level of safety.”

As the doctor went on to explain, this experience allows us to put ourselves in the shoes of the victim, minus actually going through their suffering:

“We are allowed to ask ourselves questions with an intensity of emotion that is uncoupled from the true reality of the disaster. We play out the different scenarios in our head because it helps us to reconcile that which is uncontrollable with our need to remain in control.”

As awful as it sounds, we’re often compelled by tragic events. The reason? We use them as a means of comprehending what we would do in that specific scenario.

We’re fascinated by tales of rockstars treading a precarious path between life and death, not to mention the crazy stories surrounding these dead musicians.

We love to hear about hedonistic lifestyles that we’d never want to live ourselves.

When a singer dies and we scour their back catalogue for hints that might have foretold their tragic end, it’s as if we’re getting as close as we can to the path to disaster without actually having to go down it ourselves.

Is it invasive and voyeuristic? Absolutely. But it’s also very human

Dead musicians who pass away from battles with addiction often reference their struggles in their songs – it’s part of what makes them so compelling to audiences.

Listening to them after they’re gone allows us to sit inside their tragedies, glimpsing at the signs which might have foreshadowed them through a window into the singers’ minds.

Is it invasive and voyeuristic? Absolutely.

But it’s also very human, which is why it’s something we’ve always done.

There’s a reason the Ancient Greeks held an annual five-day festival where they devoted three whole days to watching tragic plays.

Aristotle called it catharsis. Dr. Henderson calls it “confronting our fears”. Either way, it’s the same basic premise – we get something out of exposing ourselves to the dreadful misfortune of other people. In modern days, it translates into listening to the songs of dead musicians.

We’re attracted to death and disaster like moths to a flame

Ultimately, we’re drawn to death and disaster like moths to a flame. We’re death junkies, in a sense – our obsession with watching scenes of gruesome violence on TV shows like Squid Game says as much.

Maybe they give us a greater understanding of the human condition. Or maybe just a deeply-buried sense of relief that we’re not the ones suffering in the same way these dead musicians did – as cynical as that sounds.

Either way, it’s a well-documented phenomenon.

There’s something to be said for the notion of listening as a gesture of respect

We get obsessed with musicians after they’ve died – even more so if the circumstances were particularly tragic, as was the case with the likes of Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse.

Of course, there’s something to be said for the notion of listening as a gesture of respect or spikes in listening being down to big PR pushes from family, friends, and fans attempting to keep the memory of the deceased alive.

But our obsession with posthumous listening has something else behind it.

Something deeply connected to what it means to be human.