- Advertise

-

Subscribe

Let’s Call Donda What it is: Revolutionary

Critics love to hate Donda, but critics love to hate Kanye.

It’s not surprising, given the rapper’s very public support for former-President, Donald Trump, over the past few years (who was rumoured to be a favourite among choices for guest appearances at the Chicago Donda listening party).

Or maybe Ye’s declaration that ‘400 years of slavery’ was a ‘choice’ was the thing that did irreparable damage to his image, or his open support of Bill Cosby, perhaps?

Kanye’s ego-fuelled controversies give critics a long list of reasons to dislike him. It’s safe to say that the star’s reputation well and truly precedes him.

Ye’s influence on Hip Hop is transformative, Donda is no exception

But let’s not waste anymore airtime on the man or his questionable views. Like him or loathe him, Kanye has earned his spot in the ‘tortured genius’ bracket of creative society.

And he might be the first to say it, but that doesn’t change the fact that the rapper’s influence on Hip Hop has been nothing if not transformative.

Donda – however you want to define it – is no exception.

West’s late-career project is about more than the album itself – a 27 track mish-mash of styles and features spanning Kanye’s Kenyan-born ‘protege’ and the likes of HOV following his and Ye’s reconciliation.

It’s about promoting a new music philosophy – or a return to an older one, depending on which way you see it.

Essentially, it’s a drawn-out album drop full of controversial features

What made the headlines was Donda’s features which were brimming with controversies. full of seemingly unfinished songs, squabbles over features, and a whole host of controversial names along the way (think DaBaby, Marilyn Manson, Chris Brown).

But it’s not an untrue one, if you allow yourself to look past your distaste for the whirlwind of consumerism and conflicting ideologies that is Kanye West, instead focussing on the thought process that sets his latest endeavour apart.

Donda focuses on work-in-progress philosophies and optionality

Before recording was a thing, music was a fluid and changing phenomenon. That’s the spirit Donda seems to invoke, with its focus on work-in-progress philosophies and mixing optionality to optimise the listening experience.

In the past, songs were there to be sung; live music performance was the lone method of listening. The idea that there was a fixed way a song was supposed to sound was a far-off development, coming in the wake of new production technologies that gave us the ability to capture a moment and keep it just so.

West gave this fluid vision a go with his 2016 album, The Life of Pablo, publicising song edits and changes to the tracklist in the runup to its release.

But fans just seemed confused about the whole thing at the time, taking to Twitter to express their annoyance at changes made to tracks they preferred when they heard them the first time around.

Fans have always had a shaping influence on music trends, but no one gives them credit

The thing they were missing is that this was the whole point of the exercise.

The first time around isn’t the only time around. Music, like all creative processes, doesn’t have a sweet spot which you strive towards to make a song the best possible version of itself.

In the runup to Donda, with Tweets emerging showing Kanye’s producer, Mike Dean, reading the rapper comments from a fan Discord as he made the finishing touches to the album, it was hard not to appreciate the appeal of a different approach to creation that closed the gap between listener/artist and finished piece/work-in-progress.

Fans have always had a shaping influence on music trends, but no one gives them credit. The industry is keen to preserve an image of the musician as a creative genius on a different plane of existence, far from their lowly listeners.

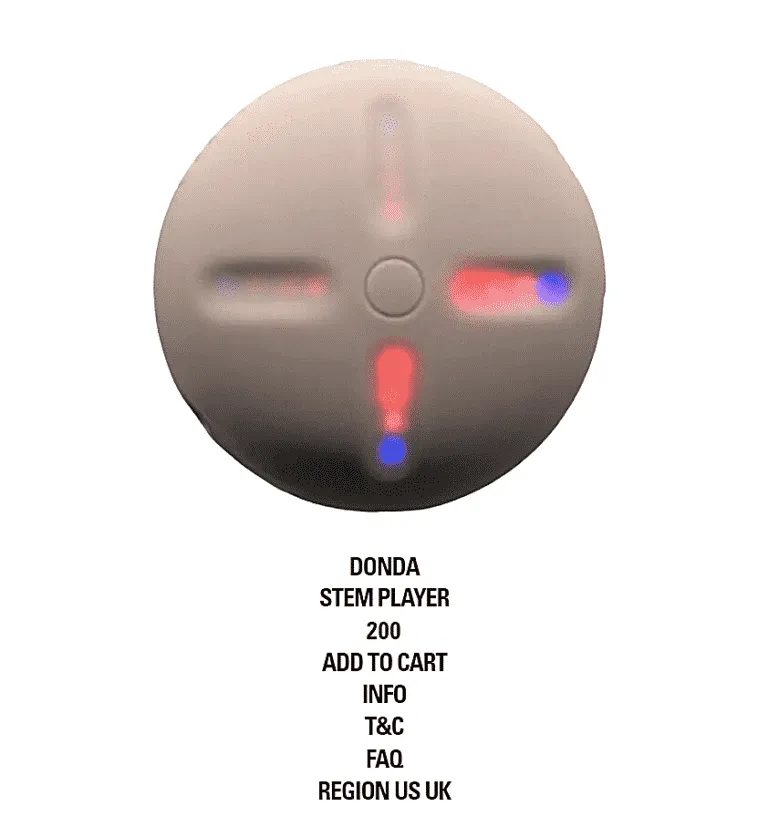

But fans are a creative force in themselves, as West’s ‘Donda Stem Player’ exemplifies.

The device allows listeners to hear Kanye’s album a different way every time they play it, if they choose to make use of its four touch-sensitive faders that allow you to adjust the vocals, bass, drums, and general ‘other’ audio of West’s tracklist (or any song you choose to upload to the device).

Our world is fixated on archiving moments rather than living them

The whole concept revolves around diversity of choice. You might find a set of adjustments that changes the mood of a track from hype to holy; you might stumble upon a pumping bassline you never paid attention to in the original.

Just because you like something you find, doesn’t mean you should never experiment with other versions. The impulse to take something we enjoy and preserve it is a symptom of a modern world that is fixated on archiving moments rather than living them.

It’s overblown to suggest that a $200 ‘Stem Player’ can fix that. If Ye’s out to change the way we listen to music in the future, a pricey piece of kit which is only accessible to those of us with a few hundred to spare isn’t going to cut it.

But you can at least admire where it’s coming from, or find what it says about the ethos of the album in general somewhat interesting.

Donda is about embracing messy trial-and-error over shiny perfection

Ultimately, Donda is all over the place (aesthetically-speaking). Its PR is the same – part-genius, part-car crash, too.

But that doesn’t detract from the ideas underpinning it: that music and streaming has been stagnant for too long, and that it’s time we embrace a philosophy of trial-and-error over perfection.

Call it ‘genius’ or call it ‘pretentious’. Either way, you can’t ignore it.