- Advertise

-

Subscribe

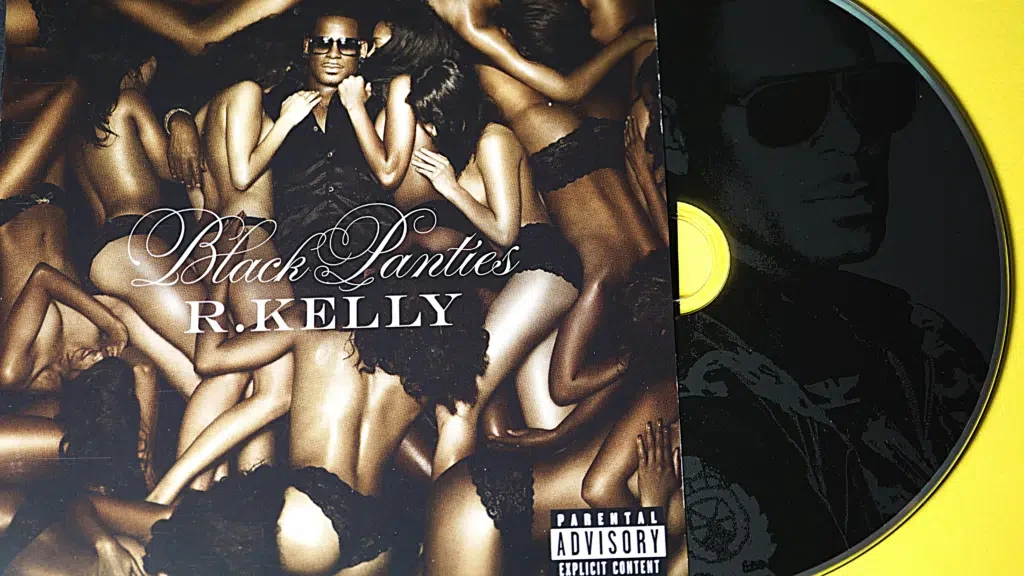

Good Music, Bad People

When R Kelly came on at a party recently, I felt like I was hearing something I shouldn’t be. ‘Remix to Ignition’ was a staple of my teenage years, but in the cold light of the star’s sexual abuse trial, it didn’t feel very nostalgic anymore.

This presented me with a dilemma: how far should I take my discomfort? I could stop singing and dancing, that would be easy enough. But what about skipping the song? Or going for a public outcry of “NEXT”? Would that spark productive conversation? Or would I just be met with raised eyebrows telling me to stop making a fuss out of nothing? Should I listen?

Bad people can make good music, after all. Humans are living, breathing contradictions.

The R Kelly hashtag was just as conflicted as I was

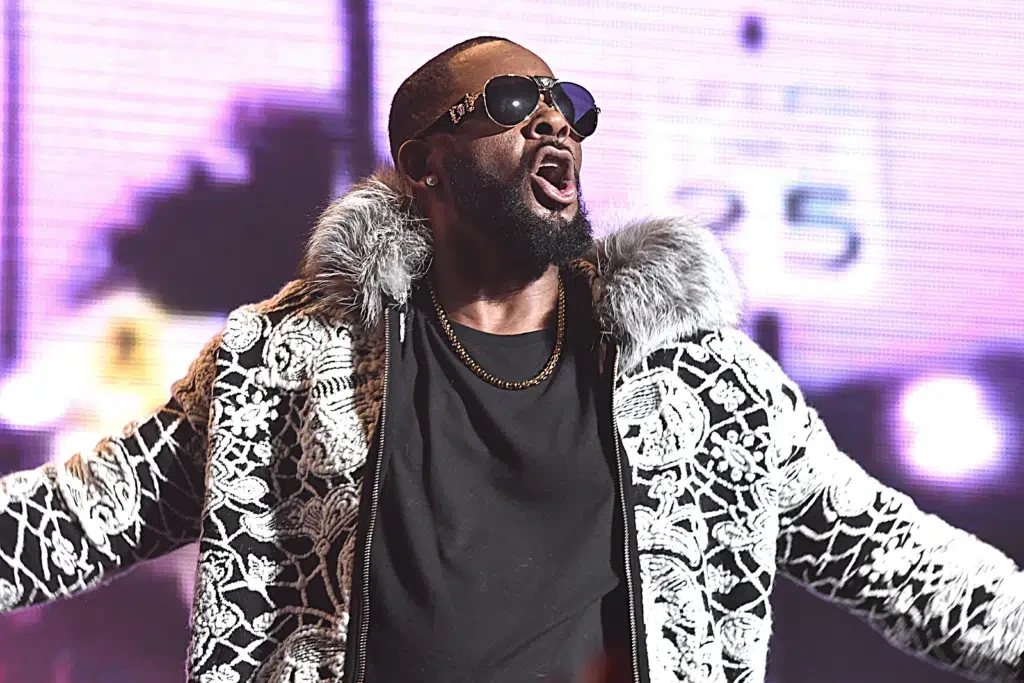

In the end, I did what any 20-something does and took to Twitter in search of an answer. Unsurprisingly, the ‘R Kelly’ hashtag was just as conflicted as I was.

Live updates of the testimonies of the singer’s underaged victims were met with calls to cancel and commend the singer at once.

‘At some point, we need to admit we should have thrown this man away nearly three decades ago when news broke that a 27-year-old R Kelly married a 15-year-old Aaliyah’ – wrote @Bossip, a black pop culture magazine.

And there lies the issue: people can’t agree on cancel culture

If the anthem of your twenties was a Gary Glitter song, can you really switch off your emotional connection to it when you know the singer was a paedophile?

If you ask your friend to skip a song at a party, are you really changing anything if the song is still available on Spotify and you know your mate’s going to listen to it when you’re not around?

And what if, like Kelly, the artist hasn’t been convicted? Are you jumping the gun if you mute them, or are you playing a part in a larger dynamic of disbelieving sexual assault survivors if you keep listening?

Some of the greatest creatives do the worst things

Putting the issue of ‘innocent until guilty’ aside, maybe we just have to come to terms with the fact that some of the greatest creatives do the worst things.

Michael Jackson has a long list of paedophilia claims against his name; Ezra Pound and Coco Chanel were Nazi supporters; even Geoffrey Chaucer – the ‘so-called father of English literature’ – went to court for being a rapist.

But we don’t hear about these people being ousted from our curriculums and radio waves because the general consensus is that the artist should be separated from their art (providing it’s good enough).

Take the release of ‘Leaving Neverland’ for example. Sure, it made Jackson a contentious topic for a while, but take a quick trip to Spotify and you’ll see just how un-cancelled the singer still is.

And yet, there’s a difference between not reading a Chaucer book and not listening to an R Kelly song. In theory, the court is the place where justice is served. But in reality, it doesn’t always work out that way.

If a musician has the power and influence to silence their accusers, public support goes a long way in breaking that silence.

In cities throughout the US and Europe, R Kelly found his tour venues cancelled and himself ‘no platformed’. As Philadelphia City Councillor, Helen Gym, declared on Twitter: not giving the stage to an alleged abuser is a mark of ‘rejecting a system that silences black women and accepts black pain. We believe survivors’.

The value of R Kelly’s music plummeted, his finances went into ruin

By refusing to play R Kelly songs, fans turning their backs on the star had an immediate impact. The value of Kelly’s music plummeted. His finances went into ruin.

And maybe this was premature, seeing as the singer hasn’t been convicted yet. Or maybe it was a long time coming, given the huge body of evidence against him and the comparably tiny percentage of sexual assault claims that are proven false.

If ‘cancelling’ an artist who is currently on trial for sexual abuse is seen as taking the side of the victim, isn’t this just redressing the imbalance of a society which stigmatises survivors and frequently lets their abusers off the hook?

You can call cancel culture ‘rough justice’. You can also call it a ‘show trial’. People always have and always will disagree on the question of where to draw the line between the person and their art because it’s just not clear cut.

There’s a difference between refusing to listen to Wagner and R Kelly

However you see it, one thing that’s not difficult to understand is that there is a difference between refusing to listen to Wagner because of his rampant antisemitism and refusing to play R Kelly because of his ongoing sexual abuse trial. The former died in 1883, the latter is still very much alive and very much affected by whether or not you choose to listen to him.

And so are his alleged victims. Which is the whole reason I asked myself this question in the first place: what should I do when an R Kelly song plays?

(In case you’re wondering, I skipped onto something else.)