- Advertise

-

Subscribe

Gentrification – from ‘Hood’ to ‘Hipster’

‘Bring in the hipsters and change the neighbourhood’. That was the mantra of Sion Misrahi, a developer/landlord who told the New York Times that renting out vacant store-fronts to bars, restaurants, and ‘counter-cultural performance clubs’ was the first step in the ‘hipification’ of New York city.

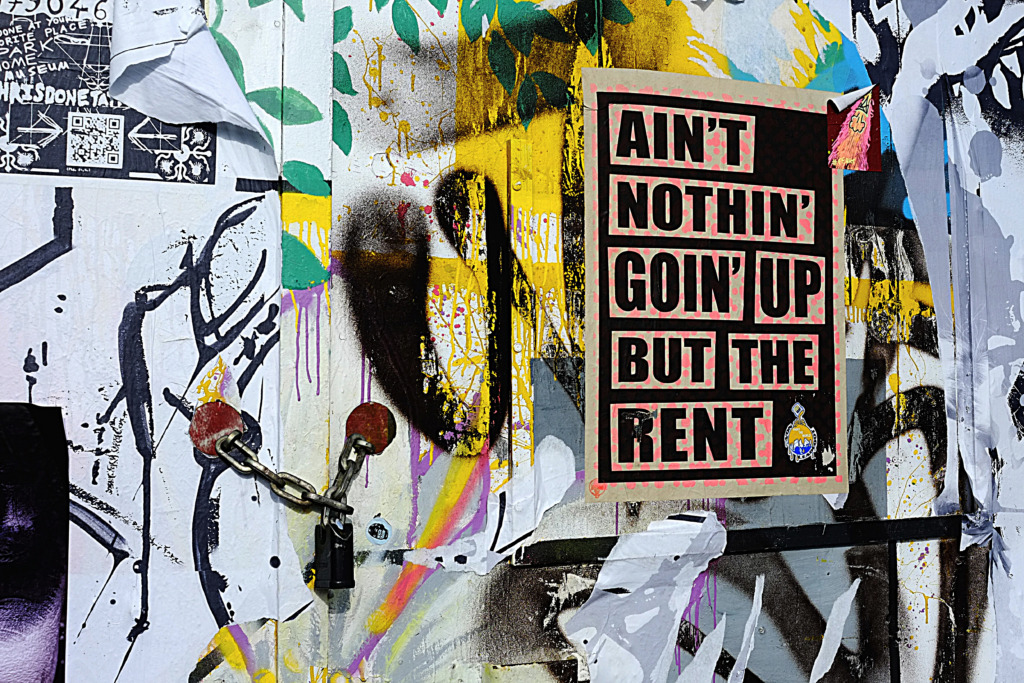

That’s where it starts. Next come the businessmen, changing demographics, inflated rent prices, and health food shops in place of the fried chicken place round the corner that you’ve gone to since you were a kid.

Ah, gentrification: a losing game for the locals but a win every time for the wealthy developers.

They start with what every twenty-something loves most: going out

So where does nightlife fit into the picture, exactly? The answer lies with Sion’s MO.

Gentrification is a process of cultural change, it’s not the same as ‘revitalisation’ or ‘redevelopment’, which seek to spruce up beaten-down neighbourhoods for the benefit of the residents who live there (purportedly).

Gentrified neighbourhoods attract new residents to them – that’s kind of their whole thing. To do this, developers set in motion a cultural shift that brings wealthy newcomers flocking to areas that have housed families through the generations, often from immigrant or minority ethnic communities.

So they start with what every ‘yuppie’ twenty-something loves the most: going out. And they run with it, as research showing the correlation between raising house prices and increasing the number of bars in an area indicates.

The very same venues are ousted once they’ve attracted the rich yuppies

In 2007, there were only six bars in Bushwick, USA. Come back ten years later (when the houses cost twice as much) and the number has rocketed to forty. And you can bet that the original six bars look very different now, too.

As Tyler Kane, an in-house booker for a so-called ‘DIY’ music-venue, Brooklyn Bazaar, pointed out – often, the same clubs that are used to attract young professionals are ousted the minute they’ve served their purpose:

“Those giant illegal clubs that closed down got away with it for a long time because it was gentrifying the neighborhood. It was like, ‘you can bring the hip, upper-middle class kids to the neighborhood because it’s cool and artsy and blah blah blah’. Then once the property value went up and people started developing, it’s like ‘get the f*ck out’.”

And so the city post-sundown transforms.

The Catch 22 of gentrification is that the thing that attracts developers to an area in the first place – its vibrant cultural buzz – is the product of the very same communities who are forced out when the rent prices swell quicker than their wages.

You’ve also got the issue of higher house prices attracting wealthier residents who put a veto on nightlife as their area makes the switch from ‘up-and-coming’ to uppity.

Sure, live music venues play a part in the gentrification process, but ultimately, they’re little more than a means to an end.

So communities are driven out, taking their dancehalls and delicacies with them to make way for overpriced coffee shops and Michelin star restaurants galore. San Francisco, Manhattan, El Poble-Sec, Camden… The list goes on, growing bigger by the day.

It’s not just the locals that lose out with gentrification, it’s everyone

But it’s not just the locals that lose out when the ‘urban renewers’ come to town. It’s everyone. When underground music venues and buzzing dancing spots are replaced by corporate chains that lack the passion and history that sets small, local businesses apart, everybody takes a massive cultural hit.

And it’s a blow often delivered by the heavy hand of local authorities – as was the case with The Dice Bar in Croydon, a music venue which specialised in black diasporic music.

Reportedly, it was told to stop playing Jamaican bashment because it was ‘unacceptable to the borough’ and ‘linked to crime and disorder’ – as a London Field Study claims (though the Met Police have since denied this).

As Marcus Harris, an ex-promoter at Madame Jojo’s – one of Soho’s most diverse former drinking spots – revealed in an interview in the same study: once an area is on a path to ‘upmarketdom’, it’s not uncommon to notice a heightened presence of local authorities cracking down on music culture:

“In my opinion, it seems that the council just used the incident [which led to Madame Jojo’s permanent closure] as a good excuse to take away the licence. If you look at the way the area is changing, they clearly don’t want a late-night drinking presence anywhere in Soho any more. They want to make Soho about families – shopping, going out to eat, going to the theatre. The bars shut at 11 and you’re home by midnight.”

London isn’t alone in this trend. Milan’s famous Old Fashion Club is set to move location in 2022 due to issues renewing its lease after a spate of incidents in the area including the rape of a 21 year old student.

Officially, the decision was made due to the ‘incompatibility of the presence of Old Fashion with the future development projects of the Triennale’. Despite the relative safety of the area and the club’s ‘high class’ reputation, it seems that these incidents might have played a key role in this decision – a development which comes in the midst of a wave of investments in the gentrification of the area.

Who gets to make the call about sacrificing the heart of a place?

Maybe the crime rate goes down; the surviving businesses can charge higher prices; the streets might be better maintained, even. But who gets to make the call about whether these things are worth losing the heart of a place and the people who made it what it was?

Not the original residents, that’s for sure.

Many have tried to resist the gentrifying boom. Rent-control policies, zoning laws, local business protection measures, and affordable housing projects are all effective measures for stopping ‘revitalisation’ from snowballing into full-blown displacement.

Thousands of petitions exist online pushing for these measures to be implemented long-term, and sometimes, they succeed in their quest to protect local people and establishments.

‘Progress’ doesn’t have to mean wiping out what was already there

Sure, fancy new bars are great. Developed infrastructure? Even better! But ‘progress’ doesn’t have to mean wiping out what was already there.

When you walk through London’s Notting Hill and see nothing but mansions and high-class juice bars, it’s hard not to think about the buzzing live music venues and vibrant dance halls we’ve had to lose to gain them.